Entitled Not Owned

🎙️ Listen to the Conversation

In-depth discussion about this topic

The Great Illusion: How Wall Street and Bay Street Convinced You That You Own Your Investments

Picture this: You’ve poured years of hard-earned income into your investments, sacrificing vacations, delaying home upgrades, and meticulously allocating every bonus to build a secure future. Whether it’s a hardworking professional in Vancouver maxing out an RRSP with diversified stocks, a family in Calgary nurturing a TFSA filled with bonds and S&P 500 ETFs, or a retiree in Montreal watching their portfolio grow through steady contributions, that online dashboard delivers the same quiet thrill. The numbers climb, the graphs trend upward, and you allow yourself a moment of certainty: “These are my assets. My retirement. My safety net.”

But what if that’s a lie?

What if, under the law, those holdings aren’t truly yours at all, just an IOU, a digital entry representing a claim on your broker, not direct ownership of the securities themselves? And what if, amid the next financial storm, a market plunge, institutional collapse, or systemic shock, the banks and brokers you’ve trusted can legally seize those “assets” as collateral for their own mounting debts, shoving you to the end of the queue as the house of cards fall?

It strains belief, veering into conspiracy territory. Yet this isn’t wild theory; it’s etched in the opaque legalese of the layered financial world, buried in contracts and codes that billions glance over but few decipher.

Back in 1994, a subtle U.S. legal overhaul redefined investment “ownership,” a change echoed in Canada a decade later that quietly morphed everyday savers from true proprietors into mere “entitlement holders.” Brokers gained the power to pool your shares, pledge them as leverage, and blur the boundary between your wealth and their risks, forever tilting the scales in favor of the system.

This expose unravels the machinery: how it unfolded, how it operates in the shadows today, and why it threatens the financial bedrock of millions of ordinary Canadians (and Americans) who assume their savings are sacrosanct.

Because if history teaches us anything, it’s this: when the music stops, the people who think they own the assets often discover they were only renting them from a system built to protect itself first.

Your Stocks Aren’t Yours (A Quick Primer)

Before we dive deep, here’s the core revelation in bite-sized form. Think of it as the red pill for your portfolio:

1. Ownership? It’s an IOU, Not Property.

When you “buy” shares through a broker, you do not get direct title. You receive a "security entitlement," a claim on a pool held by the intermediary.

U.S.: UCC §8-102(17). Canada: Securities Transfer Acts (e.g., BC STA §95). You are not a direct owner of specific shares.

Your holdings sit in a pooled ledger, indistinguishable from others. Your claim is shared, not segregated.

2. The Pot Can Be Pledged, and Raided.

Brokers routinely pledge these pooled client assets as collateral for their own borrowing. U.S.: UCC §8-511. Canada: BC STA §105.

Banks gain control rights over the collateral. Their priority stands above yours by statute.

Broker failure gives secured creditors first claim. Clients split whatever remains, pro-rata.

3. Failure Means Fire Sale.

You “own” $500,000 in positions. Broker collapses. Creditor take rules strip the pool by 90%. You recover ~$50,000. That result is by design.

4. The Laws Changed Stealthily.

Pre-1994 U.S.: investors could hold paper certificates representing true ownership.

UCC Article 8 inverted property rights for settlement efficiency.

Canada followed 2006–2007 with provincial Securities Transfer Acts enabling fungible bulk treatment.

Faster markets replaced direct ownership with entitlement claims.

5. It’s Happened Before, and Will Again.

- MF Global (2011): $1.6B in client funds pledged; ~75% recovery after years of legal process.

- Lehman Brothers (2008): Courts upheld secured creditor priority over client entitlements.

- Maple Bank (Canada, 2016): Pooled positions disputed under creditor waterfall rules.

Bottom line: You’re not an owner; you’re an uncompensated lender to a fragile system.

All modern rights are surrendered beneath the soothing deception of convenience. If this sounds alarming, good, it should. Now, let’s dissect how we got here.

The Mechanics: How True Ownership Morphed into a Fragile Claim

Step back to the 1990s, when paper stock certificates were still a thing. If you bought shares, you could register them directly with the issuer, holding tangible proof of ownership. It was clunky, slow, but ironclad, your name on the company’s books meant those assets were yours, protected from your broker’s missteps.

Fast-forward to today: Click “buy” on your app, and what happens? No certificate arrives. Instead:

-

You Become an “Entitlement Holder.” Your broker credits your account with a “security entitlement”, a bundle of rights (dividends, voting, sale proceeds) enforced against the broker, not the issuing company.

-

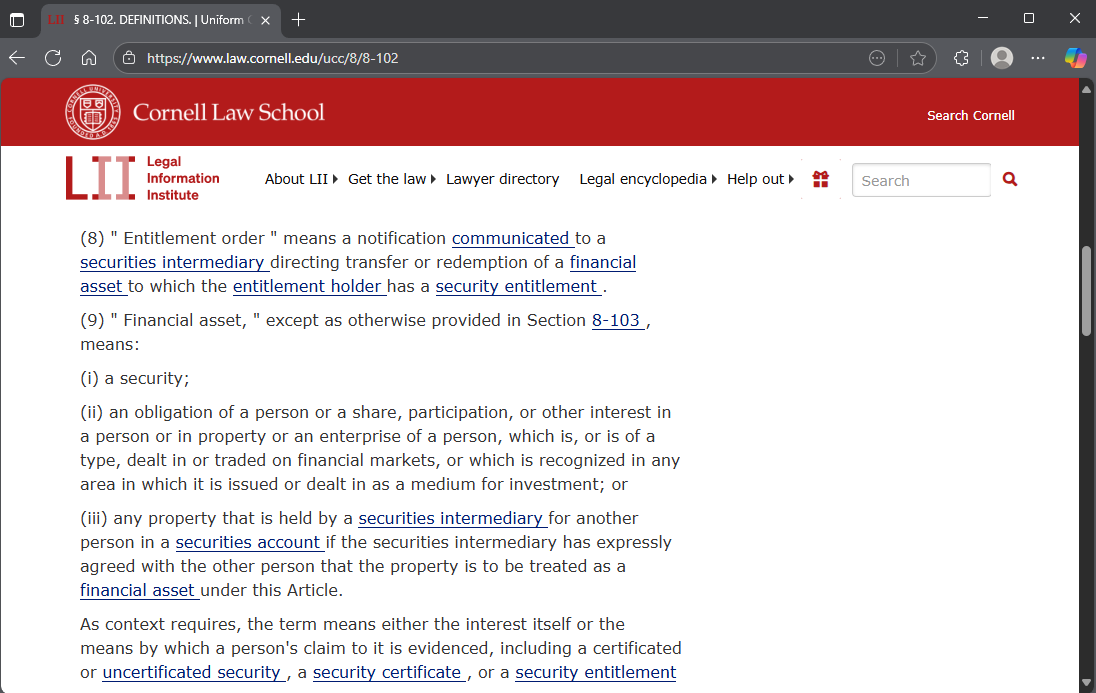

The term “Entitlement Holder” first appears explicitly in § 8-102(a)(7) of the Uniform Commercial Code Article 8 (UCC Article 8, investment securities) as amended in 1994. An entitlement holder is any person who has a security entitlement with an intermediary—usually a broker or bank.

-

Dividends flow through them; votes are proxied by them. As UCC §8-102(a)(17) defines it:

“the rights and property interest of an entitlement holder with respect to a financial asset.”

-

In Canada, provinces echoed this in Part 6 of their Securities Transfer Acts (e.g., Manitoba’s C.C.S.M. c. S60).

Plainly: You’re a claimant in their system, not a direct owner. Recourse is contractual, not proprietary, you can’t storm the issuer’s door demanding your shares when it matters.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/ucc/8/8-102

https://www.law.cornell.edu/ucc/8/8-102

This shift wasn’t accidental. Before provincial STAs (adopted 2007–2010 in all Canadian Provinces), Canada treated investors as direct owners via certificates or common-law trusts.

Legislators justified the change as “modernization”: Harmonizing with U.S. Article 8, enabling book-entry transfers, and reducing uncertainty in dematerialized holdings at depositories like CDS. (See Ontario’s Bill 41 debates.)

But the real driver? Making collateral pledging reliable for a digital, high-speed market.

The Broker Pools Everything.

No ring-fencing for your shares, they join a giant, undifferentiated pile (UCC §8-503; BC STA §97). You own a pro-rata slice, regardless of when you bought in.

Example: Broker holds 100,000 shares of Apple for clients; your 1,000 is 1% of the soup.

No labels, no segregation unless you pony up for premium service.

In Canadian Securities. law: All interests are “proportionate… without regard to” acquisition timing.

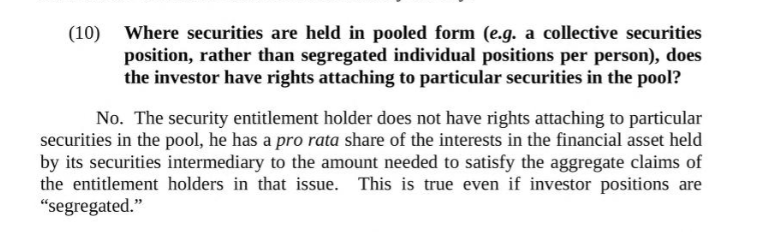

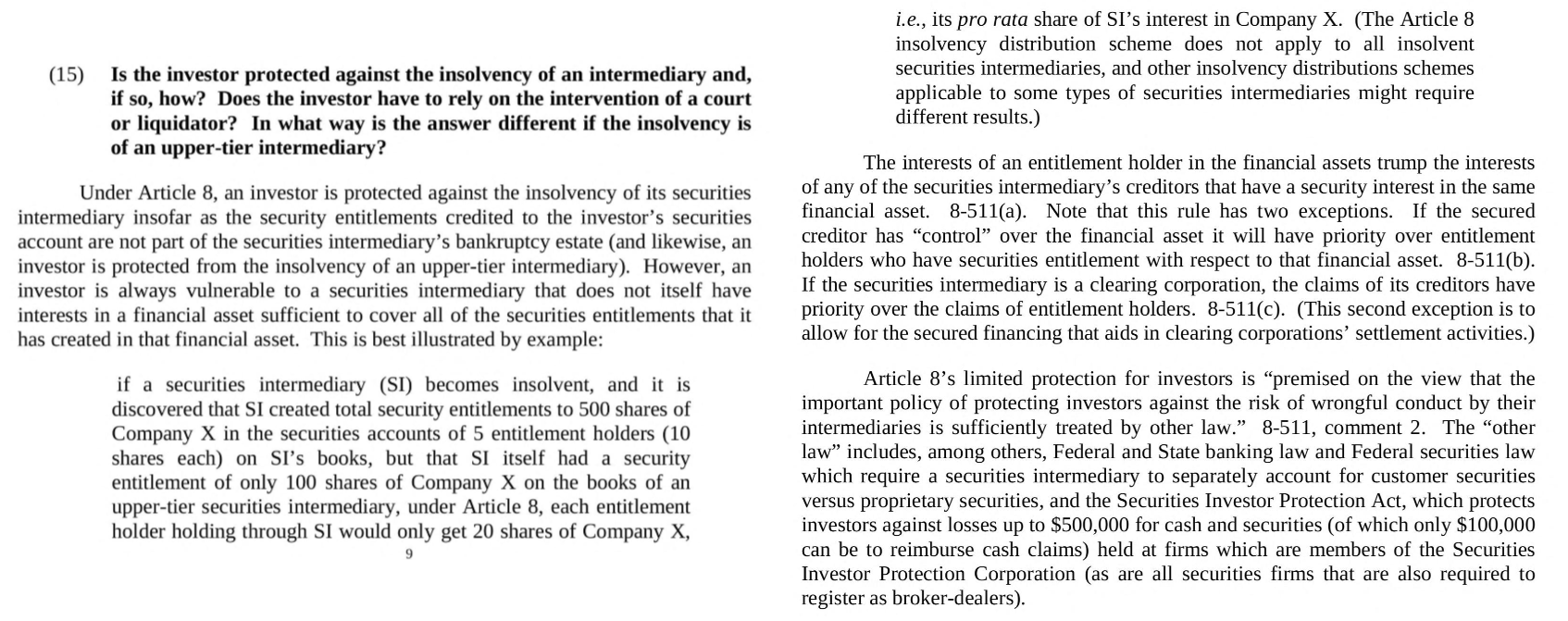

Below is a transcript from the New York Fed’s reply to being questioned from the EU Commission in 2005; straight from the horses mouth:

EU Commission: (10) Where securities are held in pooled form (e.g. a collective securities position, rather than segregated individual positions per person), does the investor have rights attaching to particular securities in the pool?

NY Fed: No. The security entitlement holder does not have rights attaching to particular securities in the pool, he has a pro rata share of the interests in the financial asset held by its securities intermediary to the amount needed to satisfy the aggregate claims of the entitlement holders in that issue. This is true even if investor positions are “segregated.”

https://archive.org/details/ec-clearing

https://archive.org/details/ec-clearing

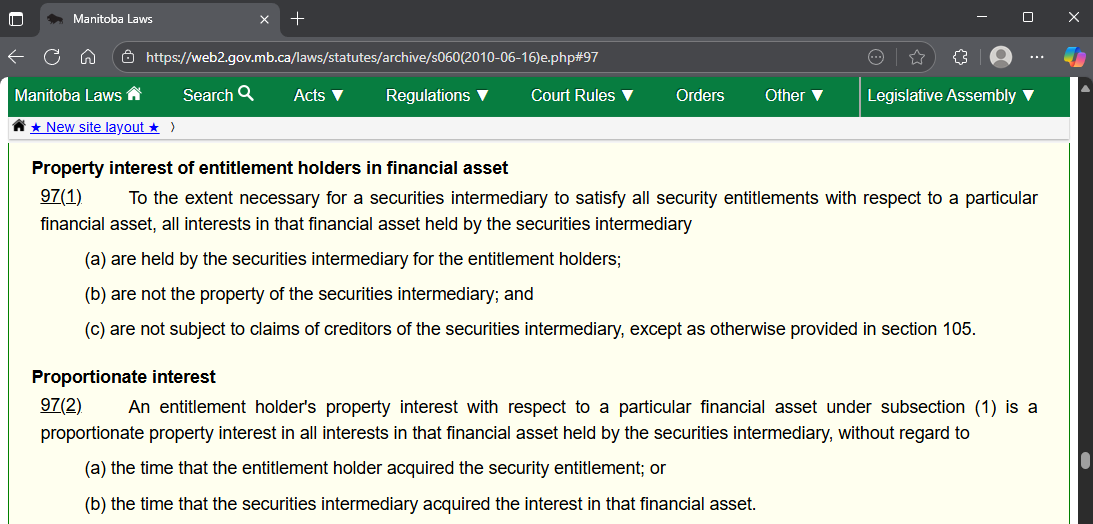

Here’s the Trapdoor

At first, laws like Canada’s Security Transfer Act §97(1) sound protective, with wording stating the pool isn’t the broker’s property, immune to their general creditors.

(b) are not the property of the securities intermediary; and, (c) are not subject to claims of creditors of the securities intermediary, except as otherwise provided in section 105.

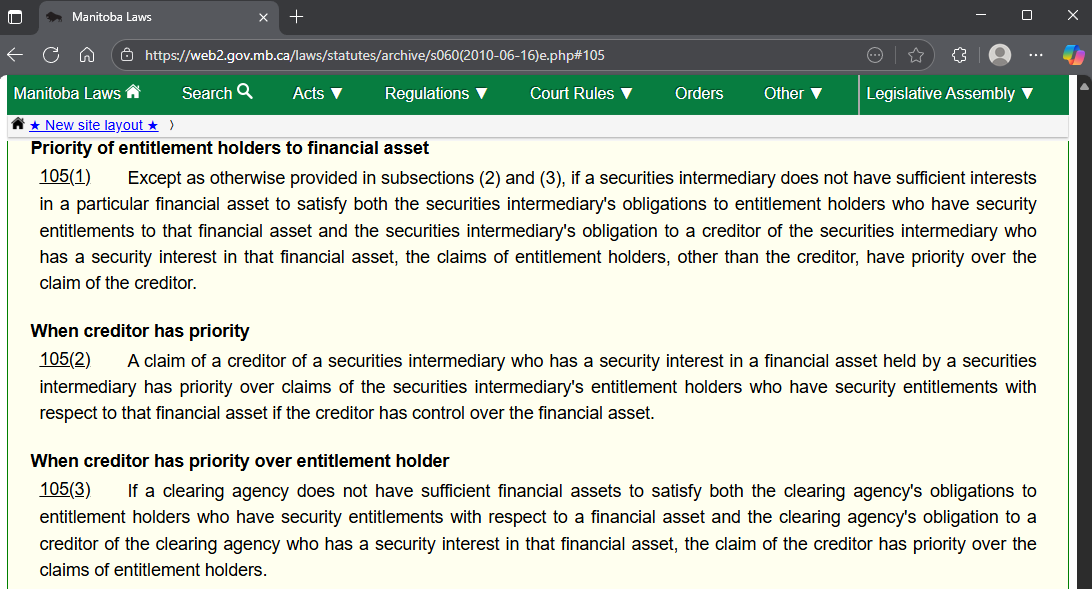

But five words gut it: “except as otherwise provided in section 105.”

Scrolling down to Section 105…

105(2) A claim of a creditor of a securities intermediary who has a security interest in a financial asset held by a securities intermediary has priority over claims of the securities intermediary’s entitlement holders who have security entitlements with respect to that financial asset if the creditor has control over the financial asset.

105(3) If a clearing agency does not have sufficient financial assets to satisfy both the clearing agency’s obligations to entitlement holders who have security entitlements with respect to a financial asset and the clearing agency’s obligation to a creditor of the clearing agency who has a security interest in that financial asset, the claim of the creditor has priority over the claims of entitlement holders.

https://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/statutes/

There you have it. When shortages hit, secured creditors with “control” leapfrog you (§105(2)–(3)). This is by design, not defect:

Your “ownership” yields to their balance sheet.

Vivid example: Envision your stock holdings as precious metals deposited in a shared bank vault. You’ve purchased and “own” your specific metals, but the Bank mixes them indistinguishably with everyone else’s in a massive, communal pile, then pledges the entire trove as collateral for their own massive loans. When the bank collapses under debt, secured creditors raid the vault first, hauling away the lion’s share. You’re left scrambling with fellow depositors to divvy up the scant remnants on a pro-rata basis, your claim reduced to mere fractions of what you thought was securely yours.

The Collateral Machine: Your “Safe” Investments Fueling High-Stakes Risk

It’s sold as “efficiency,” but the real objective is simpler: to convert your assets into usable collateral for brokers and banks. They don’t just safeguard your securities, the system is engineered to mobilize them instantly, especially in moments of stress, like a keystroke, bypassing courts or judicial oversight. By the time you demand your funds, the chain of custody has already executed. Your assets are rehypothecated.

How It Works in Canada

- CIRO rules (formerly IIROC) explicitly allow brokers to pledge “unpaid client securities” for their own bank loans (Rule 4312(2)). This pulls them out of protected segregation and into rehypothecation.

- Even fully paid shares aren’t safe. 2024 guidance permits brokers to lend them out (with your “consent” often buried in fine print).

- Bulk segregation means all client shares of the same type, whether from margin accounts or not, are dumped into one pool. They’re tracked internally, but the entire pool can be pledged at the ledger level.

- At the clearing level, CDS’s “pledge function” lets banks borrow against omnibus accounts, including yours.

- Daily (and soon intraday) margin calls under NI 24-102 pull from these shared pools.

- CIPF protection only exists because the risk is real: it covers “missing property” when firms collapse under encumbrances.

Bottom line: Even if you owe nothing, own your assets outright, your shares can fund the broker’s bets. When those bets fail, you’re exposed.

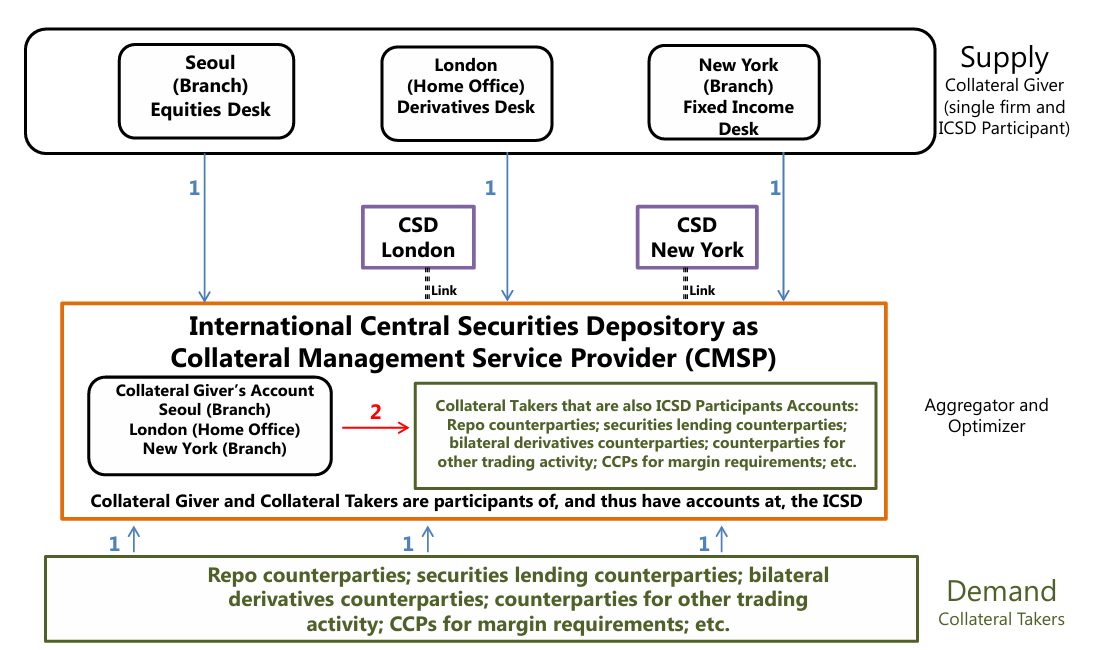

The Global Collateral-Control Architecture

This isn’t just Canadian, it’s a coordinated global system linking national depositories (like CDS) to giants like Euroclear and Clearstream. The goal? A single, real-time boarderless view of all securities worldwide.

Bank for International Settlements (BIS): Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures; Developments in collateral management services. Sept 2014

In times of market stress, rapid deployment of available securities may be crucial in mitigating systemic issues. For instance, with better visibility of available securities and better access to them, firms may be better positioned to rapidly deploy securities to meet margin needs at CCPs in times of increased market volatility or to pledge to central banks in emergency situations to gain increased access to the lender of last resort. … The automation and standardisation of many operations related to collateral management … on a market-wide basis … may enable a market participant to manage increasingly complex and rapid collateral demands.

https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d119.pdf

Translation: Your assets are emergency fuel for the system.

Why the Surge in Collateral Demand?

Post-2008 rules mandate central clearing for derivatives, a $699 trillion market (BIS 2024). This creates constant, massive collateral needs. Your TFSA? It’s not savings. It’s a shock absorber for Wall Street’s gambles.

Global Collateral-Control Architecture: The 6 Key Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Fact | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Derivative-Driven Rules | Post-2008 laws require central clearing of derivatives, spiking collateral demand (BIS data). | Regulators rewrote the system to feed the derivatives beast with endless collateral. |

| Depository Linkage | National depositories connect to Euroclear/Clearstream for a “single view of all securities” (BIS). | No asset is hidden. Every share is visible and reachable globally. |

| Client Pooling | Broker-held securities are pooled unless you pay for individual segregation. | Your shares aren’t yours—they’re part of a communal collateral pot. |

| Automatic Mobility | Securities move “free-of-payment” across borders via harmonized legal rails. | No consent, no compensation. Assets vanish instantly if needed. |

| Secured-Creditor Priority | Derivatives counterparties get first claim on collateral in failures. | You’re last in line. Big players get paid; retail gets scraps. |

| Crisis Activation | BIS: Systems enable “rapid deployment” to CCPs/central banks during volatility. | Crash = auto-seizure. Your assets are pre-wired for emergency extraction. |

https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d119.pdf

The Essence

This is a global infrastructure that treats every security in custody as potential collateral for the derivatives market. Ordinary investors think they own their assets. In reality, secured creditors have legal first claim, and the system is built to deliver your assets to them instantly when the music stops.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode

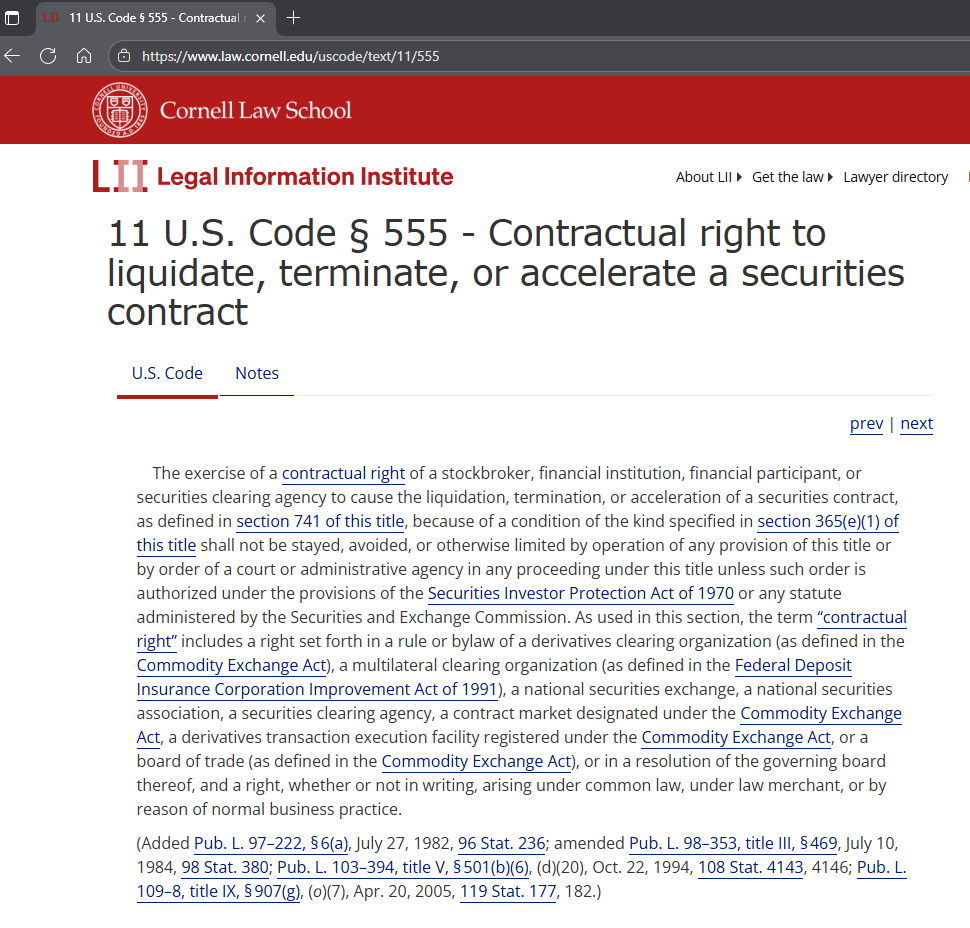

Bankruptcy Day: Safe Harbors That Sink Investors First

When failure strikes, “safe harbor” laws ensure the system survives, at your expense.

In the U.S., these Bankruptcy Code carve-outs (e.g., §555) let counterparties terminate, net, and seize collateral instantly, bypassing the automatic stay. Born for futures in 1982, expanded to swaps and repos by 2005, they prioritize “systemic stability” over individual claims.

Canada mirrors this: The Payment Clearing and Settlement Act enforces netting; insolvency laws exempt “eligible financial contracts” for close-outs. In a bust, street counterparties net and grab pledged assets first, often your pooled holdings, before retail shortfalls are tallied.

For you: Accounts freeze, positions port if inventory matches credits.

Shortfall? Pro-rata scraps, capped by SIPC/CIPF (e.g., $500K U.S., $1M Canada per category).

Margin accounts get netted against debts; fully paid ones help only if truly segregated (rare).

Court precedent seals it: In Lehman’s 2008 bankruptcy, JPMC, as a “protected class” financial institution, invoked safe harbors to seize collateral.

The judge ruled: These are “systemically significant transactions” exempt from upset, affirming banks’ priority. No executives faced charges for client asset losses; instead, it set the stage for “only they will end up with the assets.”

Who holds record title? Not you, depositories like DTCC (U.S.) or CDS (Canada), as nominees.

Your broker’s statement? Just a credit in their books. CDS operates the hub, pooling for speed and netting, but in stress, safe harbors favor counterparties over your “entitlements.”

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: Chapter 11 Case No. 08-13555

The Court agrees with JPMC that the safe harbors apply here, and it is appropriate for these provisions to be enforced as written and applied literally in the interest of market stability. The transactions in question are precisely the sort of contractual arrangements that should be exempt from being upset by a bankruptcy court under the more lenient standards of constructive fraudulent transfer or preference liability: these are systemically significant transactions between sophisticated financial players at a time of financial distress in the markets – in other words, the precise setting for which the safe harbors were intended…

The Court first must consider whether JPMC is eligible for protection under section 546(e). That subsection, like the safe harbors generally, applies only to certain types of qualifying entities. Specifically, section 546(e) covers pre-petition transfers made by or to a “financial institution” or “financial participant” in connection with a “securities contract.” 11 U.S.C. § 546(e). JPMC, as one of the leading financial institutions in the world, quite obviously is a member of the protected class and qualifies as both a “financial institution” and a “financial participant.”

https://www.nysb.uscourts.gov/sites/

Only “a member of the protected class” is legally empowered to take customer assets in this way. Smaller creditors, or you the entitlement holder are not similarly privileged.

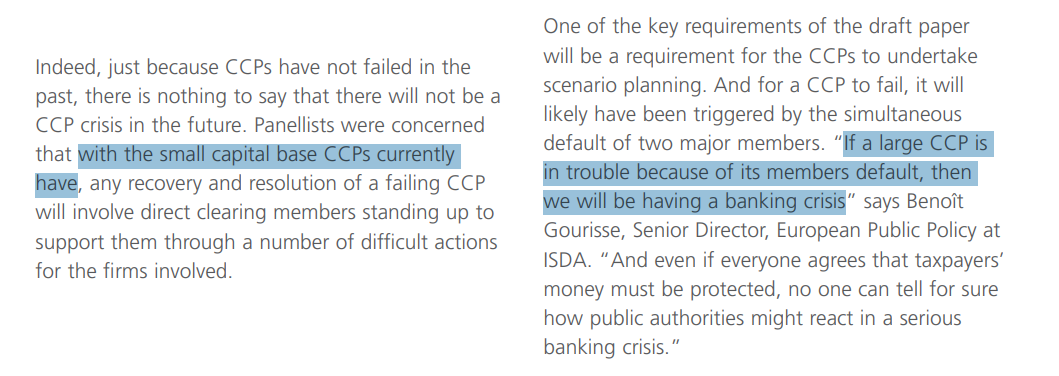

The Hidden Giants: Central Clearing Parties and Their Fragile Foundations

Enter CCPs: Middlemen like DTCC, OCC, and CDCC that clear trades, netting exposures to reduce risk. They step in on defaults, using posted margin to cover losses. Sounds stable? Think again, they concentrate systemic peril.

Euroclear’s 2020 panel warned: Risks now bottleneck in CCPs, with tiny capital bases (DTCC’s $3.5B equity vs. trillions underpinned).

https://www.euroclear.com/content

https://www.euroclear.com/content

FSB/BIS 2022 reports dodged full-crisis modeling, but if two major members default amid banking turmoil, it’s game over, no taxpayer bailouts, per EU rules. Instead, secured creditors seize underlying assets.

DTCC’s plans: Wind down failed CCPs, transfer services to new entities using pre-funded capital. But with “fungible bulk” holdings, your pro-rata entitlements lose to creditors in insolvency (Fed opinion).

The New York Fed’s reply to questions posed by the EU Commission regarding clearing and settlement:

https://archive.org/details/

https://archive.org/details/

Overall: CCPs are under-capitalized by design, primed to fail and hand your collateral to the “protected class.”

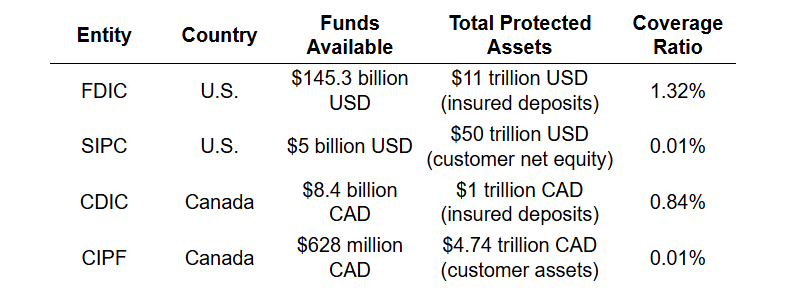

…Hold on, what about protection funds? Laughably thin:

Crunching the Coverage: Pennies on the Trillion

Let’s break it down with simple math, using the latest reported figures as of mid-2025. These aren’t pulled from thin air; they’re from official reports, extrapolated for growth trends. The table below shows the stark mismatch between funds available and total protected assets. Coverage ratio? That’s reserves divided by assets. Underfunded percentage? What you’d lose in a hypothetical 100% wipeout (ignoring assessments for now, as we’ll dissect why they fail).

For every dollar of your assets under CIPF’s umbrella, they’ve got about 1.3 cents ready to go. A $100,000 shortfall? You’d get back roughly $13 if the fund exhausted evenly, though in reality, it’s pro rata across all claims, echoing the pooled entitlements we unpacked earlier.

FDIC has a $100 billion Treasury line of credit, bumping potential coverage to about 2.2% max. But during the 2008 GFC, the fund dipped negative, forcing emergency borrowing and fee hikes on banks. Imagine that scaled to today’s $11 trillion in insured deposits, a 30% drawdown could vaporize reserves overnight.

It’s like insuring a $1 million house with a policy that caps at $1,000 after the deductible, fine for a leaky roof, useless in a blaze.

These cover pennies on the dollar in a systemic crash. Assessments and lines exist, but exhaust fast, like in a Great Depression rerun.

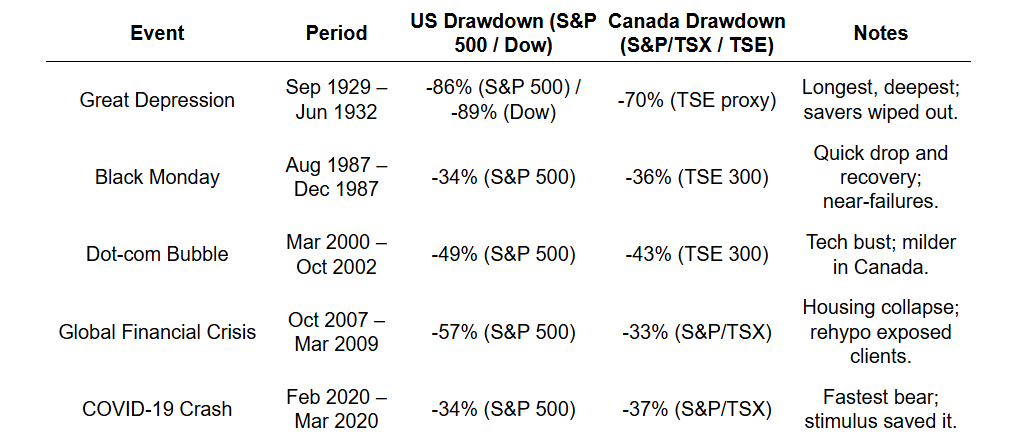

Lessons from the History

In the grip of the 1930s Great Depression, over 9,000 U.S. banks shuttered their doors, vaporizing the deposits of millions of ordinary savers who had treated their accounts as secure vaults, only to discover they held mere unsecured IOUs against failing institutions. Entire families saw lifetimes of scrimped earnings erased in bank runs and liquidations, leaving them penniless amid soup lines and shantytowns.

Yet, in a brutal twist, their debts endured unscathed: mortgages, farm loans, and personal borrowings remained fully enforceable, often leading to foreclosures and evictions that amplified the human toll, a stark lesson that birthed the FDIC in 1933 to prevent such asymmetric ruin, which we now know, is nothing more than a fart in the wind during the next meltdown.

Markets crash in predictable rhythms, but today’s entitlement-based system amplifies the pain by triggering asset seizures when drawdowns expose broker leverage (typically 10-15x), breaching capital rules at 5-15% drops and spiraling into margin calls, defaults, and pro-rata client losses.

At 20-30% plunges, individual firms seize rehypothecated pools; beyond 40%, systemic cascades hit CCP waterfalls, liquidating collateral en masse.

Your assets vanish down this chain:

Broker (pools and pledges) → Prime Broker (rehypo for prop trading and funding) → CCP (posts as margin to cover exposures) → Default Auction (firesale to surviving members) → The Protected Class (grab via priority control, leaving you with scraps)

Real-world failures illustrate the carnage: In Lehman Brothers’ 2008 implosion, $40B+ in client securities were rehypothecated and frozen for months, with UK clients losing up to 50% as banks like JPMorgan seized collateral first under safe harbors.

- MF Global’s 2011 collapse saw CEO Jon Corzine misuse $1.6B in segregated client funds as collateral for risky Euro debt bets, leading to pro-rata recoveries of about 75% after years of litigation.

- Archegos Capital’s 2021 blowup involved $20B+ in leveraged swaps; prime brokers like Credit Suisse and Morgan Stanley liquidated seized positions, booking $10B in losses but prioritizing their claims.

- Peregrine Financial (PFGBest) in 2012 hid $215M in client shortfalls through forged statements, vaporizing futures accounts; Refco’s 2005 fraud-fueled bankruptcy delayed $4B in client recoveries amid $430M holes.

These underscore how the “protected class” (banks, CCPs, regulators) leverages your collateral for daily operations, share lending, $4-5T repos, and propping up a $699T derivatives market, only to seize it in crises, cementing your spot at the queue’s end.

The “protected class” (banks, CCPs, Fed) uses your collateral for free capital, lending shares, backing repos ($4-5T daily), propping derivatives ($699T notional). In collapse, they seize via control, leaving you last.

Potential Trigger Events

• Broker Margin Call / Insolvency

Brokers facing losses pledge pooled client assets (securities entitlements) as collateral to banks or lenders for short-term loans.

In a failure event (e.g., Lehman Brothers 2008), secured creditors seize collateral first, leaving clients delayed or with partial recoveries.

• Systemic Crisis

Market crashes amplify defaults. “Safe harbor” provisions (§555 U.S.) allow counterparties to liquidate pledged collateral instantly, bypassing client claims (e.g., MF Global 2011).

Clearing and settlement failures occur when central counterparties (CCPs) demand more collateral. Undercapitalized brokers tap client pools to meet obligations, heightening systemic exposure.

• Beyond Derivatives

Rehypothecation supports repo markets ($5T+ daily U.S. turnover), securities lending ($2T+ global), and prime brokerage leverage for funds.

Derivatives (~$700T notional) amplify systemic risk as collateral chains tie retail entitlements to global liquidity plumbing.

• Counterparty Default in Repo or Securities Lending

Brokers rehypothecate client securities in repo or lending programs (e.g., short-seller arrangements). If a counterparty defaults—failing to return securities or post adequate collateral—the broker faces a shortfall.

To cover losses, brokers may liquidate pooled client assets. Repo market contagion during 2008 magnified such failures, leaving client entitlements subordinate to secured claims.

• Excessive Margin or Leverage Abuse by Broker

Brokers over-leverage client accounts through margin lending, using entitlements as collateral for their own or other clients’ trades.

During volatility spikes, cascading margin calls can trigger mass liquidations—erasing portfolios even when underlying assets remain sound.

Instances of “churning” and unsuitable margin practices have led to arbitration recoveries following broker misconduct.

• Operational or Settlement Failures

Settlement mismatches or delayed trades cause brokers to temporarily use one client’s securities to fulfill another’s delivery.

This prevents original owners from selling during downturns and has resulted in lawsuits over missed exits and opportunity losses.

• Interest Rate Shocks or Funding Squeezes

Rapid rate hikes (e.g., 2022–2023) increase broker borrowing costs, forcing additional client collateral pledges to maintain liquidity.

If paired with market downturns, this creates insolvency risk where secured lenders seize pledged assets first—seen during historical money market freezes.

Triggers Beyond Derivatives: Other Markets Propped Up

• Shadow Banking and Money Markets

Rehypothecation powers non-bank intermediaries such as hedge funds and money market funds by enabling repeated reuse of collateral in short-term funding chains.

This lowers financing costs but creates structural fragility in liquidity provision outside regulated banking channels.

• Over-the-Counter (OTC) Trading Markets

Bilateral bond, FX, and commodity trades depend on re-used client collateral for margining.

This enables higher leverage and position sizes but exposes entire collateral chains to counterparty defaults when no central clearing exists.

• Fixed Income and Bond Markets

Government and corporate bonds are frequently rehypothecated through repo agreements to sustain market liquidity and trading depth.

This integrates retail entitlements into institutional credit exposure, linking ordinary investors to systemic counterparty risk.

The Likelihood of Catastrophe: Weighing Rare Risks Against Everyday Conveniences

The failures described; broker insolvencies, counterparty defaults, and systemic collapses, sound remote, almost academic. Yet the history of financial markets shows they recur often enough to warrant more than casual concern. These events are low-probability on an annual basis but high-impact when they occur, and their frequency increases under certain macro conditions, excess leverage, rising interest rates, and opaque collateral chains. The risk is not theoretical; it’s structural.

Historical Frequency

Major broker-dealer failures are statistically rare but non-trivial in cumulative impact. The U.S. Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC) has conducted roughly 330 liquidations since 1970, averaging fewer than seven per year. The majority involved small firms, but the few that collapsed systemically, Lehman Brothers in 2008, MF Global in 2011,set precedent for how client assets can evaporate in rehypothecation chains.

In Canada, the Canadian Investor Protection Fund (CIPF) has dealt with only a handful of member insolvencies over five decades, typically contained without significant fund depletion. By contrast, general corporate bankruptcies,roughly 300–400 monthly in Canada and 40,000 quarterly in the U.S.,show that failure is a constant feature of capitalism, even if it seldom strikes the intermediaries holding retail assets.

Systemic Cycles

Crises follow a pattern. Historical data places their recurrence interval between seven and fifteen years: 1987, 1998, 2000, 2008, 2020. Harvard research finds that rapid credit expansion and asset inflation precede crises with roughly 40% probability within three years.

The European Central Bank’s Composite Systemic Risk Indicator has been rising, reflecting elevated vulnerabilities in shadow banking and regional credit networks. As of 2025, global debt and derivative exposure exceed prior-cycle peaks. Even if current dislocations appear “idiosyncratic,” as Goldman Sachs’ David Solomon recently claimed, the structural fragility persists. Statistically, a 5–10% annual probability of a systemic event is a conservative estimate.

The Trade-Off: Efficiency Versus Fragility

The indirect holding system exists for a reason. By pooling securities and enabling rehypothecation, it provides the liquidity and velocity that make modern markets function. Without it, transaction costs would revert to 20th-century levels, trading would slow, and diversification via ETFs or index funds would become prohibitively expensive. The system democratized investing, cutting trade costs from dollars to fractions of a cent, enabling global asset access from a smartphone. Like air travel, the convenience persists because the crash rate is low, even if the consequences of failure are catastrophic.

Structural Exposure

The problem is not price risk; it is title risk. Investors believe they own their shares. Legally, they hold “security entitlements” under UCC Article 8 and equivalent Canadian statutes,claims against intermediaries, not direct ownership. These entitlements can be pooled, pledged, and seized by creditors in a broker insolvency. In liquidation, clients are unsecured claimants behind secured lenders and clearing counterparties. Recovery is pro-rata, often delayed for years if lucky enough to recover anything.

Most investors remain unaware, assuming regulatory insurance provides full protection, though it only covers limited cash or securities shortfalls, not systemic collateral seizures.

Transparency Deficit

The industry conceals these realities through complexity and omission. Broker disclosures bury critical clauses inside 50-page agreements, never plainly stating: “Your assets may be used as collateral for our obligations.” Regulators tolerate the obfuscation because the system depends on client complacency. Real transparency would erode confidence, yet the moral hazard of ignorance ensures the next failure will again “surprise” the public.

Reform Imperative

At minimum, brokers and regulators should mandate direct, plain-language warnings at account creation,akin to health disclaimers. Investors should be told explicitly that in insolvency, their retirements they’ve spent their entire working career paying into, stand below secured creditors. Pop-up disclosures, concise summaries, could close the knowledge gap. The indirect system may be a necessary compromise between efficiency and safety, but informed consent is the bare minimum condition for its legitimacy.

Summary: What it means for an entitlement holder if the broker fails

- Your statement shows credits, not ring-fenced certificates; you have a pro rata claim on a pooled bulk.

- Regulators freeze accounts and attempt to transfer client books to a solvent dealer.

- Street counterparties settle first under safe harbour, they can close out, net, and seize pledged collateral immediately.

- If the broker’s inventory equals client credits, positions are ported to a new broker.

- If there is a shortfall, you receive a pro rata value claim, not specific shares.

- Investor-protection coverage may fill part of the gap; amounts above limits fall into the unsecured creditor pool.

- Uninvested cash is treated like other estate claims, subject to the same waterfall and limits.

- Margin accounts were collateral already; liquidation or transfer occurs after dealer obligations are netted, balances can be reduced or negative.

- Fully paid positions help only if actually segregated and not rehypothecated; otherwise they are part of the shortfall.

- Timing is not yours to control; netting and porting occur on regulatory and clearinghouse schedules before you are notified.

Breaking the Chain: Your Action Plan to Reclaim Control

Here’s how to protect what’s yours:

- Direct Registration (DRS): Transfer shares to the issuer’s books in your name. No pool, no pledge. Feasible for U.S. stocks via services like Computershare; limited options in Canada.

- Demand Segregated Accounts: Contractual ring-fencing. Higher cost. Rare for retail but exists.

- Avoid Margin and Lending Programs: Cash accounts only. No consent, no rehypothecation.

- Read and Question Disclosures: Confirm hypothecation status, omnibus vs segregated control, pledge rights.

- Diversify Brokers: Distribution across CIRO members limits single-point failure.

- Monitor Coverage: Confirm active CIPF membership.

Key: Quiz your broker on account type, rehypo practices, control agreements, and governing STA. Demand transparency.

In flow: Buy direct → Skip entitlement → Avoid pools → Break pledges → Survive shortfalls.

The law favors liquidity over you, but knowledge is power. Your retirement isn’t collateral, treat it like the fortress it should be.

-

Disclaimer

The information provided on this website is for general informational and educational purposes only. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, investment, tax, or legal advice. All opinions expressed are those of the author based on publicly available information and personal analysis. Readers should conduct their own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor, accountant, or other professional before making any investment or financial decisions. The author assumes no liability for any actions taken based on the content of this site.